Memory has stretch marks. Although many would like to throw 2020 into the junkyard of oblivion, the truth is we will remember it. It will be like those who recalled the epidemic of 1800 when, according to historian Cornelio Lopez Espinosa “people walked down the street, suddenly sneezed, and lay there.”

In 1812, in the hopes of ending the epidemic, the Lord of the Column was brought to San Miguel de Allende from Atotonilco for the first time. This year the statue has magically reappeared in the Church of San Juan de Dios—without bustle, festivities, or fireworks, and without the faithful accompanying it on its journey here. But Lord of the Column’s festival was celebrated in the heart of every devotee. Father Dante announced in April that the statue will remain in the church until the pandemic is under control.

Centuries-old traditions are changing. The Holy Burial was memorialized, but in a closed procession, with the Resting Christ remaining within the Oratory Church. This year, the celebration of the Holy Encounter was also different. To the surprise of locals, the elders from the Parroquia carried the cross around the Jardin Principal. San Miguel’s centuries-old customs and traditions are part of the collective imagination; locals look forward to them, and visitors enjoy them. Another one is the Fiesta del Valle del Maíz, where a sense of community and brotherhood prevail, filling the area with music, fireworks, particular smells, colors, and flavors. This celebration has been postponed and is scheduled to take place on September 14, which is Holy Cross Day.

September is full of celebrations. One is the declaration of the Virgin of Loreto as Patron Sublime of the town of San Miguel el Grande—now San Miguel de Allende. It is also the month of the Cry for Independence and the reenactment of the entrance of the insurgents into town. There is also the festival in honor of the city’s patron saint—Saint Michael the Archangel—and La Alborada—the offering of lights. Further, the Guanajuato International Film Festival is in September.

One hundred twenty thousand

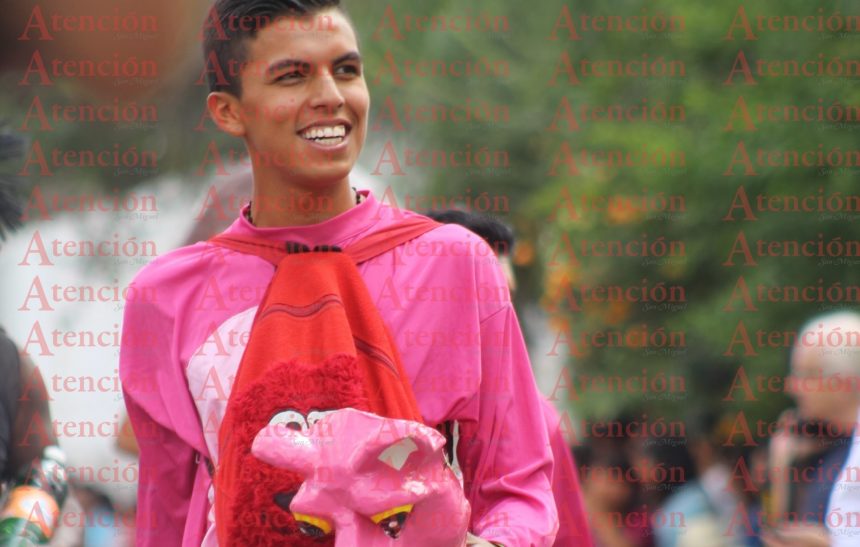

Every year, on the first Sunday after June 13, the sidewalks along the streets of Centro begin to fill with people of all ages. Many set up seats or bring cushions to sit on. Starting at 8am, costumed participants begin to stream into town in tinsel-covered cars along Ancha de San Antonio and Salida a Celaya, on the way to their meeting points. At the same time, a mass is celebrated in the atrium of San Antonio Church.

It is a day when the town goes crazy, no matter the heat, the humidity, the jostling, or the stamping—nor whether you are among the locos or the observers. In the midst of all this there is always the possibility of rain, but to this day rain has never dampened this festival. All is joy, festivity, and music. Sweets fly through the air to be eagerly caught in overturned umbrellas or by children who call out for them with cries of “Sweets! Sweets!”

City authorities said that in 2019 there were eight thousand costumed participants. They came dressed as whimsical creatures, characters from fairy tales, magical realism, movies, and nightmares. And 120 thousand people came from all over the country to see the show, which can only be characterized as “crazy.”

At a meeting that included government officials, members of the clergy, and leaders of the traditional groups that participate in the Locos parade it was decided to cancel the event this year. Jorge Vidargas, head of the city’s Sanitation Department II, explained that local people and those from near and distant cities come for the annual parade, and that Covid-19 cases have continued to increase. Since the event is so highly attended, the flow of people could not be controlled, so social distancing would be impossible to enforce. The event was cancelled because of the possibility of greater contagion and a potential peak in local infections.

Blessing of the pilgrims

Traditionally, starting a fortnight prior to the Locos parade, pilgrims from the 28 rural communities and the 10 neighborhoods that are part of the parish come to the parish Church of San Antonio de Pádua. This year it will be different, however. According to the parish priest, Antonio González, a sculpture of a pilgrim will be installed in an open car and it will head a simple caravan that will travel to each community and neighborhood to offer a blessing. The priest will take part in the caravan.

Every June 13, pilgrims’ sculptures of San Pascual Bailón (to whom the Locos parade was originally dedicated) are taken from calle Nueva toward San Antonio. This year, though, this procession, as well as music, fireworks, fairs, and other attractions have been canceled.

September was proposed as an alternative

Those in charge of the cadres (each cadre is made up of 13 groups), Jorge Baeza, Patricio Espinosa, Josué Patlán, and Fernando Peralta, all agreed with the cancellation. They acknowledged that conveying the message to the participants was painful because so much work goes into preparing for the event throughout the year. Work begins early, with each cadre deciding on a theme. Then the construction and painting of the sculptures, structures for the parade, costumes, the masks, and everything else needed is undertaken. Each cadre member has a specific task.

The Soria family cadre, for example, will store the sculptures they use in their parade in a trailer. The Montiel family will lay away the mask molds. The Cholucos family’s creative mojigangas will be set aside, as will the work of members of El Cachir family. The decrease in work around creating the Locos parade has impacted the local economy, although all the materials can be used next year.

Jorge Baeza said the office of Culture and Traditions proposed a date in September for the parade, but the group declined. He commented, “The Locos party is in June, and it does not change.”

Los Locos started with gardeners

In the past, San Miguel was surrounded by orchards, including in the park. Pears, apples, plums, and other seasonal fruits were harvested. Every year at harvest time, the orchards’ proprietors opened their doors to all the workers and their families to come and eat all the produce they wanted. There were also religious celebrations in the churches, when people dressed up as gardeners in overalls, boots, long-sleeved shirts, and hats. They all danced in honor of San Pascual Bailón.

Eventually others became attracted to the dances and celebrations and started gathering to watch. The gardeners realized that their dance space was being encroached upon and came up with an idea to disperse the public. They put on grotesque masks to scare the onlookers away. They also began to carry animals that might keep people away—skunks, ferrets, pelicans, armadillos and other strange creatures. And that is why people started calling them “locos”—crazies.

From these beginnings, groups, or cadres, formed to continue the religious festivities as a tribute to San Pascual Bailón, and the Locos parade began. The Sunday chosen for the parade was based on the saint’s festival day, June 13. San Pascual Bailón is worshipped in the parish of San Antonio, where his statue used to be kept. It now resides in the Church of San Juan de Dios.