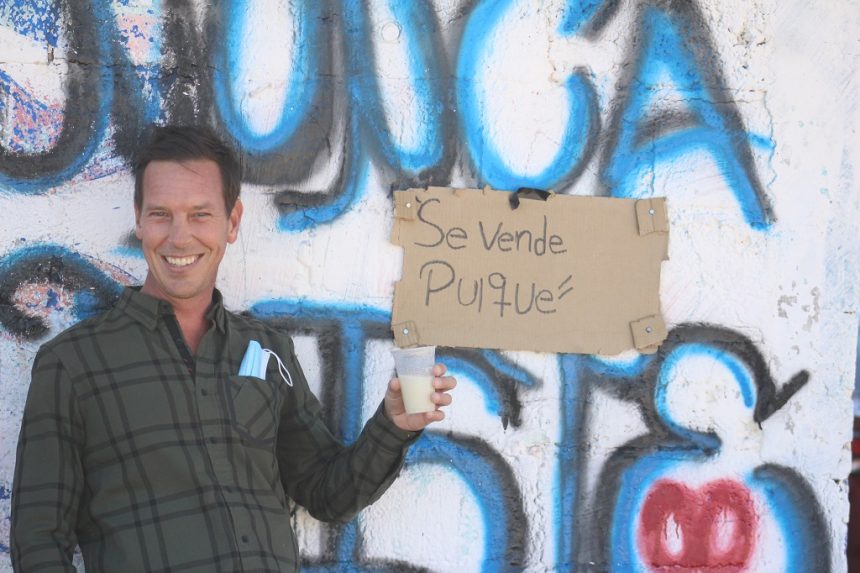

During the contingency, producers of aguamiel (mead) and pulque (a traditional alcoholic drink made from fermented aguamiel) claim that sales have increased. They believe it is not because people are drinking more, but rather that they grasp the benefits of the beverage. On the arid land of eastern San Miguel, maguey pulquero plants grow abundantly, and the stories the cultivators tell are as old as the fields. One just has to ask Doña Santiaga “Chaga” in La Aurora, Juana in La Joyita, Doña Helena in Puerta del Aire, or Don Manuel García in El Membrillo. They know the land, they love their fields, they know how to make pulque, and they sell it to whoever requests it. Of course, if you are going to take the pulque route while consuming pulque, you have to be careful because the saying “you knock me down” may have an effect.

Pulque production changes depending on the season. Some producers, like Doña Elena, claim that from April to June the magueys “suck themselves dry” and don’t produce aguamiel. By contrast, “La Wera” Urbina says, “Magueys work 24/7/365. The only difference is that during the dry season the aguamiel is less sweet because the maguey absorbs more minerals.”

In La Aurora, from the heart of the maguey to your jug

The maguey pulquero that grows in the center of Mexico has historically surprised many foreigners, according to the Cultural Information System of the Government of Mexico. The art of the tlachiquero (the person who extracts the aguamiel) consists of removing the upper stalks and piercing the heart of the maguey, creating a bowl in which the aguamiel can pool. When fermented, aguamiel becomes pulque. Foreigners are surprised by the great variety of products that can be obtained from the maguey. The stalks can be used to wrap barbacoa (a traditional method of slow-cooking in a hole in the ground), to make paper, for decoration, for roofing, and for fencing. Fiber extracted from the stalks is used to make rope, shoes, and sewing thread. The thorns are used like chopsticks to eat prickly pears, as nails or for pricking things. The quiote (flowering “trunk” that sprouts from the center of the maguey) is used as a roof support, or can be cooked and eaten. The plant can be burned, and its ash used to heal wounds, make bleach, or even as food for cattle.

Santiaga López was born in the Cerritos community in 1953. “I am totally a country woman,” she told Atención. She arrived at La Aurora (Ejido de Laguna Escondida) in 1970. There, her mother-in-law showed her how to plant the maguey, how to break it apart and prepare it to extract aguamiel. Of Doña López’s children, some went to Texas, some stayed, and others who had left returned home to tend and work the maguey.

Chaga, La Wera’s mother, commented, “Because of how my in-laws taught me, I saw that it was important to take care of this plant that the earth gives us. I have passed that knowledge on to my children, who are now working to preserve this millenary tradition.” Today the family cultivates 16 hectares of maguey. Forty-six years on, she has three varieties of maguey: baby corn, pencón, and verde.

Chaga says that it is important to be careful that the maguey does not flower; if that happens, there will be no aguamiel. “The plant is ready when the top of the stalk gets thin,” Chaga told us, pointing to a plant. Then it is time to prepare the opening. Choosing the best side of the maguey, the thorns—which can measure up to 10 cm long—are removed, the thin part of the stalk is cut with a machete, and a bowl is formed into which aguamiel will pool after a few days.

When the aguamiel starts running it must be extracted up to three times a day. One plant can produce up to 10 liters per day. How is the liquid gathered? With a rudimentary tool, the acocote (a type of gourd). The bowl, which can be covered with a penca (maguey stalk) is uncovered, the acocote is inserted, and the tlachiquero sucks as much aguamiel into the acocote as possible—up to two liters. The hole at the bottom of the gourd is covered with your fingers, and the gourd is emptied into a container.

Once the aguamiel is extracted, it is strained and stored in a glass container for 40 days. Then it is emptied into a clay jug, in which it ferments. A little aguamiel is added daily. Aguamiel and pulque should be enjoyed fresh from clay jars, as that gives it a different flavor.

To accompany the pulque, Doña Santiaga believes that nothing is better than some nopalitos (diced paddles of the prickly pear cactus) with pico de gallo and beans from the pot. The beverages go with all Mexican food, including mole. Producers say that whether or not someone gets drunk on pulque depends on one’s mood, as well as what one is doing.

La Wera, who gives tours of the maguey plantation in English, explains the benefits of the plant, and how aguamiel can be a substitute for water in many foods. “It’s like medicine. the secret is how you combine it. To contact the family and see the process, call Wera Urbina on 415 115 9899.

Right at Puerta de Aire

It is almost certain that whoever visits the community will find the adorable Doña Helena walking on the road wearing a hat, pants, checkered shirt, and with a machete in hand going to the plantation to help her husband Manuel extract the aguamiel. Following the road beyond Jalpa heading towards Charco de Sierra is a sign that reads “pulque for sale.” It can be bought to go, or to drink there. If you gain Doña Helena’s trust, in addition to explaining the benefits of the drink, she will tell you her story and even invite visitors to tour her backyard, where memories live on.

In a hut where she lived for about 20 years and raised her 10 children is her old tortilla press, the corn mill, and memories of when she arrived. “I lived on the hill, and I got married there. Our wedding was simple; we did not rent any tables or chairs. A bower was made for the bride and groom and petates (mats made of woven palm leaves) were laid under it. There, on the floor, just the bride and groom and their families ate. There was not enough money for music.” She sells a liter of pulque for 25-35 pesos. When we toured the plantation she told us, “The fields are very kind, and if we take care of them, they produce and take care of us.”

La Joyita

From the road that leads from Puerta del Aire to Jalpa you can see the mountains, as well as goats, horses, and sheep grazing. You would never imagine that up on the mountain, in the middle of endemic trees, is the small community of La Joyita.

Juanita, a strong, hard-working woman who loves the countryside, lives there. She knows how to make pulque de tuna (from prickly pear cactus) and pulque de los magueyes. Together with her husband, Alex, she also sows the land from which they harvest corn, beans, and squash. This gives them sustenance during the year, and they sell the surplus. She milks her goats and makes artisan cheese from it. She harvests chiles in a small organic garden, and makes red salsa in a molcajete (traditional Mexican stone mortar) to eat with “delicious bean tacos with nopalitos and goat cheese.” She climbs the monumental magueys and extracts the aguamiel for making pulque.

“I have lived in the city, but I will always love the country,” she told Atención. “An uncle took me as a wetback to the United States to take care of a baby. After two years I came back to Mexico, and have stayed here. Here we lack nothing; the land is productive if you know how to work it. Here you sing, you shout, there is no stress, you are happy, and you live with nature,” she continued. Next to the house (the property extends to the river) is her plantation of magueys and nopalera, the goats and the pig pens. Everything is a cycle, she says; they feed goats with stubble, the pigs with nopales and prickly pears. “We don’t need anything here, we are happy.” Visitors to Juanita and Alex’s plantation can enjoy a delicious country meal there. To contact Juanita, call Rossana Álvarez at Vía Orgánica 415 153 7091.

El Tigre

Don Manuel García lives in El Tigre. He remembers that when he was a child—he’s now in his 70s—there was no school. He took care of “10 burros, but I don’t know what they were for, 10 horses, 30 head of cattle, goats, and sheep.” His parents always took care of the fields, and from his father he learned how to make pulque. “When we got home from work, we didn’t drink water, my father was waiting for us with a jug of pulque. Don Manuel talks about how at the age of 12 he planted his first maguey. “I liked pulque,” he says.

Don Manuel took us to his plantation and showed us how to harvest aguamiel, which can be extracted from the maguey when it is five years old. The mouth of one maguey was covered with a stone and a sack. Once he extracted the aguamiel, he added it to a bottle of pulque so that it would be ready to drink in about 30 minutes. His house is next to Rancho Vía Orgánica.