Art Opening

“Memento Mori”

Paintings by Linda Laino

Sat, Oct 30, 12–5pm

La Huipilista Artspace

Julián Carrillo 1, Colonia Guadalupe

By Lena Bartula

“Everything that has a beginning has an ending.

Make your peace with that and all will be well.”

These words were penned by American author, Buddhist monk, clinical psychologist, and meditation teacher, Jack Kornfield. They appear at the bottom of Linda Laino’s Mandala Calendar image, which I see every day on the wall in my studio. Looking deeply into Laino’s work, it’s tempting to imagine that one knows more about her and her theme, Memento Mori, also the title of her upcoming exhibition at La Hupilista Artspace.

A meditation practitioner for many years, Laino, like many artists, has long viewed her painting practice as meditation. “The process of creation—making something tangible from an idea or imagining—is one of constant evolution, with little ‘deaths’ occurring throughout the making of a painting.”

The phrase Memento Mori, Latin for “remember death” has its roots in ancient Rome. The Stoics, the Ancient Romans, the Buddhists, and other traditions, have all extolled the virtues of practicing dying before death. Laino’s painting of this concept began years ago. Her intention was to explore not only the ephemeral quality of life but by extension, the ephemeral qualities inherent in the art-making process. The idea that life and death are encountered simultaneously in the painting process renders it transformative. “And what is death, if not transformation?” she asks.

Picasso, Dali, Cezanne, and Van Gogh have all used skulls or skeletons in their work in order to contemplate death. Sometimes called “vanitas,” these paintings also used images of rotting fruit, hourglasses, and watches as direct symbols of fleeting time.

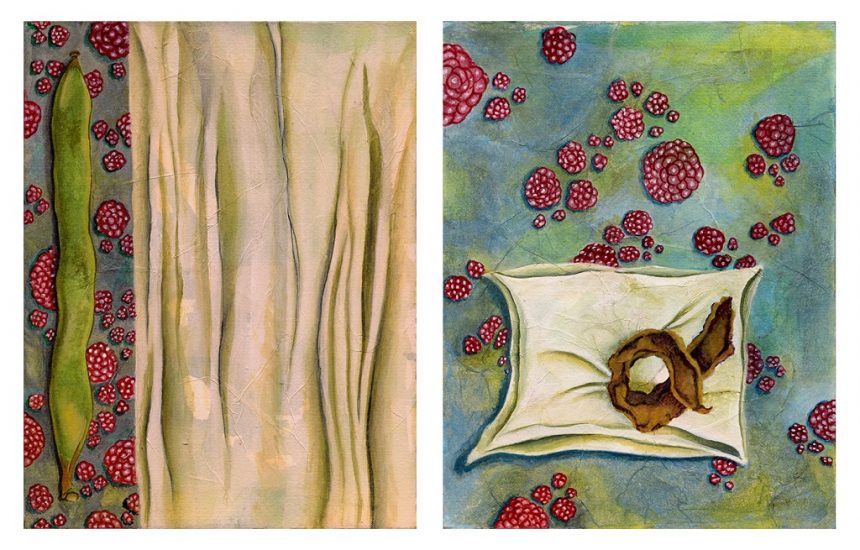

Laino looked to nature and its incremental decay as a way of framing this idea. According to the artist, “Decay is a fascinating process. The changes in form, color, and pattern are myriad. The question becomes, ‘What is the true form of this thing in the end?’”

She began the series at a residency in France where she found specimens on walks in various stages of decay. “It became important to me that the flora and fauna come from the same area where I was making the work,” she says. This also functioned as a way of connecting her and the work to a place. Laino says this series was conceived as a tight body of work, asking her to intentionally limit the imagery, color, and compositional scope. Most of the artifacts are placed on folds of fabric. With fabric’s own important connection to death rituals, she elevates a dying leaf or flower’s importance to suggest a sense of “laying them to rest.” The work—all watercolor and ink on rice paper—is mounted and hung in grids. The grid format gives each stage of decay its individual dignity and completeness while also reminding the viewer of the connectedness to the whole.

It is auspicious to present this exhibition during the observances for Day of the Dead here in Mexico. Becoming witnesses to death—others’ and our own— we acknowledge its presence, passage, and power, reminding us of the impermanence of everything. Exploring the process of decay alerts us to its form of beauty as in the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi; that beauty is defined in part by flaw or change. Laino hopes viewers will see decay and death as no less a beautiful process than birth and renewal and recognize the grace, elegance, and melancholy of time’s effect on all things, both living and man-made.