Legacy

If you wish to consider a donation for the Library’s scholarship fund in your will, please contact Robert Remak, who will provide you with all needed information on how to do this. bobremak@yahoo.com

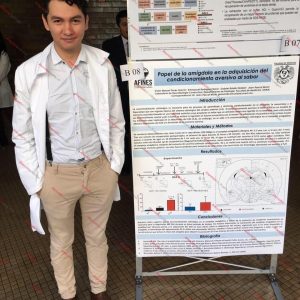

At the age of 21, Víctor Torres packed his suitcase and left for Mexico City looking to fulfill his dreams. He studies at the Faculty of Medicine of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and is about to publish his first (co-authored) research paper in The Journal of Neuroscience. He is in his eighth semester and has one course left to complete. What he recognizes is that his dream has come true thanks to a scholarship that the Public Library of San Miguel de Allende A.C. has given him.

His story is not unique; many others have taken the same route like Mariana Espinosa Deanda, who has been a nurse for 25 years at ISSTE (Institute of Social Security for State Service Workers).

Dreams and goals

Víctor Torres is now 25 years old. He gave us an interview from his modest room in Mexico City. He was born in San Miguel de Allende, and his mother abandoned a medical career when he was born. He worked for a time, until his parents decided to have him live with his aunts—with only a three-year difference between their ages—to give him better opportunities. His mother, in the meantime, managed to finish her degree in General Medicine.

Victor says that he was not the most brilliant student in elementary school or high school. He really wanted to study medicine at UNAM, but his high school average was not the best. He attempted to take the entry exam several times without preparation and failed. When he finally decided to prepare, his dedication and effort paid off, and he passed the test for admission to UNAM in the National Polytechnic College.

“My mom finished family medicine, with the promise that we would go live together. Bad decisions led to debts that she continues to pay till now. Then I had a brother. I was already 16 years old. My grandparents always supported me—my grandfather had also studied at UNAM, but when my grandmother got pregnant, he had to drop out. When I finished high school, I didn’t know what to do. We had no money. [When] my mom became independent, we left the grandparents’ house. With what she earned, debts had to be paid, the rent, [and] what was left over was for food. It was difficult, sometimes there was no food,” he said.

His grandfather is a public service driver and sometimes Victor worked with him, which motivated him to study. When he completed the entrance exam, getting 117 right out of 120 questions, he knew he could go into the Polytechnic at UNAM.

“Before entering, the first concern was economic. My grandfather told me, ‘Go. I’ll see how we do it.’” It was difficult because the rentals are very expensive for students. If you wanted something close to the university, there was nothing under 3,500 [pesos]. “Now I found a room, although it is farther from the university. The first year I had the support of my mom and my grandfather. For the second, I was worried about what I was going to do. The economic situation was further complicated at my grandparents’ house, where the greatest support came from.”

Then one day, he found out about the library scholarship and applied. “Fortunately, they gave me the scholarship,” said Victor.

He says that his dedication to study improved notably. He no longer had to go home to cook every day and then return to school. He could now eat somewhere nearby “the first thing I used [my money] for [was] food. I bought two books, an atlas of anatomy, and the other of physiology.” Víctor explains that there are many books at school but there are also many students, so some books are not always available. This is why he bought them.

“With the scholarship, the first thing I did was pay for meals. It was wonderful. I was able to go to French class,” he noted. Then he got a computer, so he didn’t have to stay late at the school library anymore. Instead, he devoted his time to laboratory research for the paper he is about to publish in the area of Behavioral Neurobiology: the Role of the Cerebral Amygdala in Aversive Conditioning of Flavors.

Before the start of the pandemic, Víctor was working at the Hospital General of México. But later it turned into a COVID facility and sent the students home. Aside from his laboratory studies, medical studies, and work at the hospital, Victor is part of the American Association of Neurological Surgery—in its UNAM chapter, and part of the Puma Medical Student League. He is also a local officer of the Mexican Association of Physicians in Training. “In this, I am now a local officer of research exchanges—we receive students from other countries and send our colleagues to other countries although the program is now closed due to the [COVID-19] contingencies,” he said.

Back to San Miguel

Victor Torres wants to continue with research and complete his doctorate in Biomedical Sciences. He reflects on his past and says he would love to return to San Miguel. “I left as [someone] inexperienced in life, very afraid of making mistakes, of deserting. I was very afraid to fail. It is not complicated. To fail would be to fail me and my family. I moved with my family’s illusion of my family (let’s see if he can make it), now my family sees me as [an object] of pride; they praise me everywhere. I want to return to help my community; I have always loved the social part. “ He would love to work on leveling academics so that that everyone could enter UNAM. “I would love to teach elementary and high school classes. Leveling and studying are the cornerstones if you want to study at university. With a sufficient level, you could reach UNAM, the elite of public universities. There is a capacity and knowledge to enter by entrance exams. It is a proposal that I have for the Library,” he concluded.

Sacrifice and learning

Mariana Espinosa is a nurse generalist at ISSTE, and the third of nine siblings. Her family had a house on Volanteros. When her parents went to work in Mexico City she remained with her brothers and took charge of the house. One of them got pneumonia, but fortunately recovered. Her father was a carpenter, and worked with Monsignor Mercadillo, the parish priest. But there was never enough money. Mariana dropped out of third grade because of the punishments that the teachers inflicted then, such as attacking the students with bricks in each hand. Later, they moved to the Santa Julia neighborhood, where “there were six or seven houses. We brought water from the Santa Cruz of San Rafael where there was a public well. Our house was made of black sheets. But sometimes there was not even enough to feed us. Her childhood was not easy. After finishing secondary school, she took a first aid course with Dr. Gordillo, and this is where she met Juanita Ruiz, her nursing teacher. “I was a nurse at night, by day I was a domestic worker.” After 10 years she met Juanita Ruiz again; she was then motivated to study nursing.

“Juanita told me that she was paying for my degree; it was about three or six months. Then if the financial situation was no longer good, she would help me get a scholarship from the Library. I was in the School of Nursing and Obstetrics, [at] the same time as getting my baccalaureate with an endorsement from the University of Guanajuato in Celaya.”

Studying was never easy, she claims. “I was leaving at 4:20am, I had to walk to Central [bus station], I was hungry .Money is never enough, and I also ran into various situations. We took the bus next to La Comer. On one occasion a person with a razor followed me. It was the risk I had to take.” She worked in social services at Apaseo although she had enough qualifications to work at Celaya. But Apaseo offered her lodging and food.

Mariana y sobrino

“Social service is hard for students. There was no staff to cover. Sometimes we covered three shifts. We had the commitment to deliver work for release to the Ministry of Health. We were preparing ourselves and this helped us qualify. We also went on consultations, training people whom we taught everything. We had that commitment. In the end some doctors offered me work with them on weekends. They had twins. Until then i had an income.

“I entered ISSTE in 1991. I am a nurse. Last year, I was re-categorized. I was working as an assistant; finally that year I started the process, and now I am a general nurse.”

Mariana is divorced and has no children. She says she has seen brothers and nephews grow up. She believes that God saw her with eyes of mercy, giving her the opportunity to serve in medicine. When she finished her degree, she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. “I was about to throw myself off the bridge of the IMSS T1 hospital in León, but I remembered how my parents prayed when my brother became ill with pneumonia. Now I believe that God put me in this office to help many people who, like me, need words of encouragement in the face of illness. The cancer, after surgery, disappeared. When you experience limitations that is when you value things. You jump over the obstacles. I am what I am now because luckily I had angels around me to help me continue,” Mariana concluded.

100 scholarships

Alma Cervantes, scholarship coordinator at La Biblioteca, told Atención that there are currently 61 college students and 31 high school students supported by the program. She commented that up until February, fewer than 70 of them received support, but thanks to the generosity of the committee, the number has increased to 75. “My job now is to ensure that we have a perfect 100 every year” and to cover this school year.

The Library provides two contributions of 2,200 pesos for each high schooler and two deposits of 4,400 pesos for university students. In addition to these, there are other incentives for outstanding students covered by additional projects—called scholarship plus. To learn more about the program, or to be a mentor, write to almaelenacervantes@gmail.com